The South East Rivers Trust regularly works towards removing weirs or installing fish passes. In the second of a series of blogs about the problems weirs cause to rivers, Dr Chris Gardner, Head of Science and Partnerships, writes about two big issues. These are the movements of fish (which he tracked for his PhD) and drought resilience. Here, he addresses some myths about both aspects.

‘Migratory’ fish? All fish migrate

It is often thought that weirs and other barriers that restrict the movement of fish only affects ‘migratory’ species such as salmon, sea/brown trout and eels, as their migrations are relatively easy to observe and are well known.

However, all fish migrate to some extent, and all fish have life stage specific habitat requirements affected by habitat degradation. Coarse (or freshwater) species such as barbel, chub and dace are affected by habitat fragmentation and degradation caused by weirs.

Higher water velocities on riffles encourages plants such as water crowfoot to grow. Plant growth on riffles makes it difficult for predatory fish to hunt. This also provides an abundant food supply of invertebrates and overhead cover that hides fish from predatory birds and animals.

Riffles are great places for baby trout and young salmon to live, they are also the preferred habitat for juvenile barbel. However, riffles hidden under lake-like habitats upstream of a weir lack the characteristics that make them great juvenile barbel habitats. And if there are low numbers of small barbel then there will be fewer numbers of big barbel and eventually no barbel at all.

Here, the trout and salmon fraternity are ahead of the game. The economic value of salmon (commercial and recreational) and the large declines in salmon populations since the 1980s have caused scientists and anglers alike to research and understand what the habitat requirements are for all life stages of these fish.

They have used this information to minimise potential population bottlenecks or limiting factors because of available habitat. There are many things impacting our fish populations, but in-river habitat is the one thing that is relatively easy to address and benefits all wildlife. Organisations such as the Wild Trout Trust have been encouraging progressive thinking and educating game anglers in fisheries management and river restoration.

Research shows why fish need to access the whole river

Coarse fish migrate and need to move around a river system to locate specialised habitats required at certain times and during certain conditions. Fish are streamlined, live in a near weightless and frictionless environment and need to constantly swim just to maintain a static position in the river. Hence, fish have great potential to be highly mobile.

Modern tracking studies using implanted radio or acoustic tags have revealed these migrations. For example, in 2010 Dr Karen Twine, of the Environment Agency, radio tracked 20 adult barbel (6-15lb) in an 8.2km reach (between two impassable weirs) of the Great Ouse for 18 months. She demonstrated that the barbel utilised most of the river length available to them and made seasonal movements to spawning and over wintering habitats.

Similarly, in 1993 Dr Martyn Lucas, of Durham University, radio tracked 31 adult barbel (2-6lb) over 15 months in a 7.2km reach of the River Nidd, a tributary of the Yorkshire Ouse, with open access to the Ouse.

Again, these fish were highly mobile, ranging over sections of river from 2-20km in length. Their movements were associated with seasonal shifts in habitat, upstream spawning migrations and their downstream migrations to ‘over wintering’ habitats in the lower reaches and main River Ouse.

Basically, fish will move as far as they are able to fully exploit the best available habitat/resources: the more limited the resources, the further they will travel.

Other studies on less fragmented rivers with more limited essential habitats have shown that fish have the potential to move over very long distances.

Study shows the benefits of free passage

During my PhD in 2006, I tracked the movements of 80+ adult common bream (4-7lb) over four years in a long 40km reach of the Lower River Witham, a very uniform fenland river in Lincolnshire.

My bream were tightly shoaled and relatively immobile in a deep tributary off the main river at the upstream extent of the reach during the winter, moving short distances of, on average, less than 5km a month up and downstream.

In the spring, they became highly mobile moving on average 30-40km a month, utilising the entire length of the river available, with one individual moving more than 120km in a single month!

At this time, they were visiting shallow tributaries off the main river, before using these for spawning in late May/early June. Once they had spawned, they spread out and spent the rest of the summer in the main river foraging, again moving on average 20-30km a month up and downstream. In the autumn, they moved back upstream to the deep tributary for the winter. This same yearly pattern was observed throughout the study.

These studies demonstrate that adult fish use different habitats at different times of the year and require free passage between them.

Habitat requirements are different for adult and juvenile fish. So, during a fish’s life it will have many different habitat requirements. These requirements will be more crucial for juvenile fishes because of their vulnerability to predators and therefore their need to find safe cover.

If any single habitat type is lacking, limiting or inaccessible, there will be consequences for individual survival and therefore the population as a whole. Weirs often restrict populations to those reaches that have sufficient habitats to enable life-cycle completion.

The “weirs” thing about drought resilience …

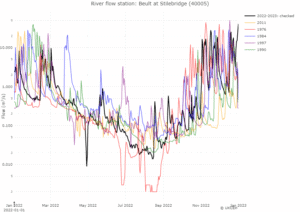

A common misconception is that weirs delay river discharge and therefore make the river more resilient to drought. Weirs do hold back a quantity of water in the upstream section, which is “impounded” – leaving the river more like a still canal or pond. However, a weir just stores water in the upstream area – and once the river is full, river flows over the weir at the same rate it enters the impoundment.

Imagine an impounded section of river as being like a kettle being filled from a tap. Once full, the kettle overflows at exactly the same rate as the tap runs and the water bill ticks up exactly the same.

In the event of drought, rivers tend to dry from their upstream end first. Impoundments upstream of weirs can and do provide refuge areas for fish in such an event. However, these areas are likely to be heavily silted because of the lack of flow, and will quickly deoxygenate because of biological processes in the silt, leading to fish deaths.

Fish will move downstream naturally in response to a drying river using the river’s flow to navigate.

However, if the fish encounter an impoundment upstream of a weir, and there is no flow going over the weir (because of the drought), there will be no flow cues to navigate by and the fish will simply be unable to move any further and become trapped where they will die as the water in the impoundment deoxygenates.

If no weirs exist fish will move downstream, seeking out deeper, fresher water in the river’s lower reaches. Once the drought has broken, they will then move back upstream.

So, perhaps counterintuitively, weirs actually reduce a river’s resilience to drought.

In conclusion, the impacts caused by weirs are problems for freshwater fish as well as salmon and trout: the principles might not be as well understood or as popular, but they are real. If our rivers are to fulfil their ecological potential, we need to address this and other factors that are limiting fish populations.